Like most life events the more work, effort and dedication you put into an activity the greater your chance of achievement and reward. Rehabilitation post injury is no different. It doesn?t matter if you are a ?weekend warrior? with a sprained ankle, a high-level athlete post surgery or an employee with chronic back pain. The more work, effort and dedication you put into your rehabilitation program the greater your chance of maximizing your post-injury function within the shortest possible timeframe.

The Devil is ALWAYS in the detail

Your body is the ultimate adaption tool and for better or worse it will adapt to whatever stimulus (or lack thereof) you expose it to. Typically optimal recovery post-injury follows a characteristic pattern:

Phase 1: Early Post-Injury or Post-Operative Phase

Phase 2: Early Functional Strengthening Phase

Phase 3: Rehab Running and Resumption of Functional Activities Phase

Phase 4: Running Intensity / Integrated Activity Phase

Phase 5: Return to Sport Phase

It is the responsibility of your exercise physiologist or sports physiotherapist to prescribe the specific exercises within these phases at the right intensity & volume. However, it is your responsibility to complete the program with diligence and accuracy. Unfortunately, patients who don?t put in the required hard work, effort and dedication get sub-par results and are usually the ones complaining that their ?physical function was never the same?.

Likewise the content of the program needs to be quality, and the devil is always in the detail. Arguably, many rehabilitation protocols in use today focus too heavily on low-loading functional sport-specific exercises at the expense of weight training. Another reason could be that the weight training intensity is indeed too low during rehabilitation in order to produce improvements in muscle size and strength (Thomee, 2012).

How should I structure a rehab program to make sure I get the best result?

During the ?functional strengthening phase? of a rehabilitation program, it is important to expose the targeted muscles to a stimulus that will promote positive adaption (improved strength, control, etc). One of the reasons elite level athletes are able to return back to their chosen sports ASAP following an injury is their access to professional supervision. Professional supervision is important because it ENSURES that all assigned exercises are completed properly and progressed as functionally able without delay. Unless you have exceptional body awareness, understanding of exercises and motivation then strictly home-based programs will not work. More commonly, a combination of supervised rehabilitation sessions and home-based exercises are ideal to ensure accuracy, diligence and understanding.

The length of a rehabilitation program will largely depend on the type of injury (acute / chronic), location & an individual?s pre-injury physical condition. The vast majority of injuries (if detected early and diagnosed correctly) can be mapped out to the week /day back to a full return to pre-injury activities. However, the reality is that age, pre-injury fitness levels, how chronic the injury is, and the location (tendon in particular) can vary and increase the time and effort needed to get the best possible result.

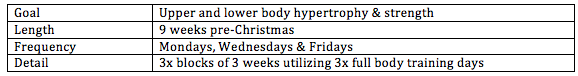

No one ever plans to fail but many have failed to plan. Thus, every rehabilitation program should have a clear plan that outlines the goals, timeframe and staged progressions. The staged progressions should detail how you will progress to your goal within the desired timeframe. Below is an example of a rehabilitation plan for a rugby player recovering from a grade 1 rectus femoris tear.

3 week optimal return to play timeframe

Stage 1 (day 1-4)

– Return ROM and manage symptoms (RICE)

Stage 2 (day 5+) – Criteria to start this stage is NO local tenderness

– Bodyweight quadriceps loading

– Introduction to exercise bike

Stage 3 (day 7-13) Criteria to start this stage is NO pain on bodyweight lunge

– Rehabilitation running (volume)

Stage 4 (day 14+) Criteria to start this stage is NO pain with 2km running volume

– Rehabilitation running (intensity)

Stage 5 (day 18+) Criteria to start this stage is NO pain accelerating to or holding 90%+ speed

– Team training

Play (day 21+) Criteria to play is completion of team training with nil issues

Supervised ?practice makes perfect?

Having an accurate plan is essential but the success of a rehabilitation program lies in the specificity of the exercises, attention to detail and practice. Detail is achieved through accurate feedback, which is the missing key separating home based and supervised rehabilitation programs. In the early stages of a new rehabilitation program it is easy to loose form and develop / reinforce bad habits. However, accurate feedback ensures the cementing of a strong foundation that you can build and progress exercises from. Only once you have demonstrated the ability to recognize incorrect technique and correct it yourself, should you begin transitioning towards self-supervision.

Arden et al (2011) found 3-27% of Autograft hamstring ACL reconstructions have hamstring strength deficits up to 3 years post op. However, current isokinetic strength data collected since February 2011 on patients who have had an ACL knee reconstruction and completed supervised rehabilitation at Elite Rehab & Sports Physiotherapy demonstrate an average return to equal strength between limbs at 16 weeks (dominant leg injured) and 24 weeks (non-dominant leg injury). These results support the impact of supervised rehabilitation and the ideology what you sow you shall reap.